by Tim Crosby

CARBONDALE, Ill. – Looking directly at the sun is almost never a good idea, but researchers at Southern Illinois University Carbondale recently used a safe, low-tech way that combines a common household item with a telescope to capture a unique image of a total solar eclipse.

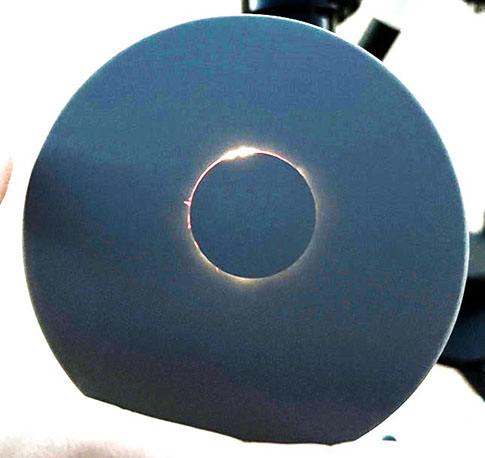

A member of a study abroad team from SIU demonstrates an eclipse image on a sun funnel. The group captured a unique image while viewing a total solar eclipse in Western Australia in April. (Photo provided)

The SIU team captured the image during a trip with students to Western Australia in April, where they witnessed a total solar eclipse. The group used a sun funnel, a simple projection device commonly employed by amateur astronomers to observe partial solar eclipses, to snap a highly detailed photo of the sun during totality.

The group traveled to Australia in preparation for the total solar eclipse that will hit SIU and Southern Illinois on April 8, 2024. As the crossroads of two total solar eclipse events in the last seven years, the university plans to play host to scores of sky enthusiasts that day, as well as media from all over the world.

Sun funnels typically are not used to image totality during an eclipse, which can be viewed with the unaided eye while the sun is completely covered. But special circumstances in Australia resulted in the exceptionally bright corona being visible on the funnel, said Bob Baer, specialist in the School of Physics and Applied Physics who helped lead the trip.

“Sun funnels are popular with solar observers conducting group outreach because they provide a safe method for viewing a partial eclipse, which cannot be viewed safely with the naked eye,” Baer said.

“The image captured by SIU is the first known image of totality to be taken on a sun funnel.”

Baer credited quick thinking by SIU students Paige Chamberlain and Kallie Heavrin for capturing the image.

A fortunate accident

Named after its main component, the contraption is made by attaching a common automotive oil funnel to the telescope’s eyepiece, allowing observers to see a detailed image of the sun and fine detail in sunspots. Instructions on how to build one were first published in 2012.

Along with the funnel, parts include a rear projection screen and hose clamps. When focused properly, an image of the sun appears on the projection material stretched over the top of the funnel.

Baer along with SIU faculty members Cori Brevik, assistant professor of practice in the School of Physics and Applied Physics, and Harvey Henson, director of SIU’s STEM Education Research Center, trained students on how to use the solar funnel and telescopes before leaving for Australia.

After driving to Exmouth, the group set up for its solar eclipse observation site. Once the telescopes were ready, they noticed the solar image on the sun funnel was too bright and realized the correct size eyepiece had not been packed for the trip.

“The students were using lower magnification 26mm eyepieces instead of the 13mm eyepieces we had intended to bring,” Baer explained. “This made the image smaller than intended and brighter. But with the eclipse rapidly approaching, we decided to leave the setup as it was.”

Plans originally called for students to remove the sun funnels during totality and observe the corona through the eyepiece. But there is some danger in doing this for inexperienced observers who might try to view it too early or too late, and this particular event was a short, hybrid eclipse with the moon just barely covering the solar disk.

“All total solar eclipses are unique, and this one was phenomenally so,” Baer said. “The moon being so closely matched in apparent size to the sun made for a spectacular sight with prominences and the chromosphere visible. The corona was large due to increased solar activity as we approached solar maximum, so it was substantially brighter than others. The sky was also exceptionally clear and dry, adding to the apparent brightness of the corona.”

Discovered after the trip

Given the potential for eye damage under all these circumstances, Brevik advised the students to leave the sun funnel in place. Both Chamberlin and Heavrin took cellphone photos of the projection during totality, not realizing that they had just witnessed and documented something unique.

Baer said it wasn’t until after the group returned home that he noticed the image was special.

“When I saw the image, I immediately contacted a colleague with a lifetime of eclipse-chasing experience,” Baer said. “He confirmed that no one had ever taken an image of totality like this.”

Baer said the image demonstrates the potential for viewing all phases of a solar eclipse, including totality, with a sun funnel. The sun funnel allows everyone in a group to view the same image and have features pointed at and explained. Observers would not all need to have their own eclipse glasses, which may be in short supply during the event.

“This is really exciting for those of us doing solar outreach and group observations, especially outreach involving youth for the upcoming annular and total eclipses in the U.S.,” he said. “First- time viewers are often overwhelmed when seeing totality and can miss important features like the diamond ring. The sun funnel allows you to see sunspots, the diamond ring, prominences, the chromosphere and the inner corona – all enlarged to a format that is easy to see.”

Observers, however, should keep in mind that viewing totality by looking directly at the corona is still an experience they should not miss, Baer said. They can also observe the few minutes of totality – when the entire disk of the sun is covered by the moon – with binoculars or a small telescope. But knowing when to look and when not to look is often confusing for people who have not seen an eclipse before.

“Seeing totality is like nothing else you will ever see,” he said.