by Tim Crosby

CARBONDALE, Ill. – Shay Valentine, a Southern Illinois University Carbondale doctoral student in zoology, is examining the spatial dynamics of native fishes throughout the Upper Mississippi River basin to acquire a wider understanding of the storied river’s ecosystem and help wildlife managers conserve its unique native fish diversity.

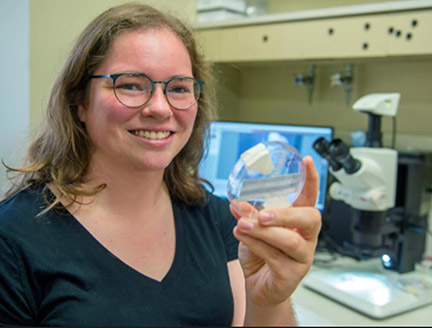

Shay Valentine works in a laboratory recently at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. A doctoral student in zoology, Valentine is examining the spatial dynamics of native fishes throughout the Upper Mississippi River basin. (Photo by Russell Bailey)

Extending from Minnesota all the way down to the farthest reaches of Southern Illinois, the basin’s system comprises an extremely complex network of streams and their watersheds, including their flora and fauna. Surprisingly little is known about how the systems and the native fishes interact.

Valentine is collaborating with multiple universities and agencies to untangle these complexities as part of larger project funded by the Upper Mississippi River Restoration Program and coordinated by the U.S. Geological Survey. Already published in top journals, including a first-authored paper in the journal Science Advances, Valentine also recently received the J. Frances Allen Scholarship Award from the American Fisheries Society, which is given to a female doctoral student based on her contributions to fisheries and aquatic science at the national and international level.

Working mostly in the laboratory on her current project, Valentine is combining various chemistry techniques to examine the habitats and diets of 12 fish species to learn more about how they use resources in various portions of the river and to make comparisons. The laboratory methods are powerful tools for answering ecological questions and improving management of the fish as well as the river.

“I’m looking at how different species of fish change their resource use spatially and across time,” Valentine said. “We’re using diet analysis, stable isotope analysis and microchemistry to describe resource use at short, seasonal and lifelong scales.”

A long-term project

Valentine started working on the project in Greg Whitledge’s lab in May 2019. Whitledge, a professor in SIU’s Center for Fisheries, Aquaculture, and Aquatic Sciences, has conducted extensive work using chemical analysis of otoliths from invasive grass carp, exposing an important clue to controlling their numbers in the Great Lakes.

Otoliths, which are tiny bones also known as “ear stones,” also come into play in Valentine’s work when looking at various fish’s lifelong habits. But in pursuit of that important “big picture,” Valentine also is teasing out information from their short-term and seasonal lives.

At the shortest time scale, Valentine uses diet analysis to determine what species such as largemouth bass and bowfin have eaten and how that differs geographically. Diet analysis allows her to identify partially digested fish, insects and other invertebrates that are important to the diets of predatory fishes, giving her snapshots of the fishes’ lives.

Pulling back to the seasonal scale, Valentine uses stable isotope analyses on eight species, examining ratios of carbon and nitrogen in dried muscle tissue and in the eye lenses of individual fish. The carbon ratios can reveal the breadth of habitats, while the nitrogen tells the story of prey eaten by individual animals and groups of fishes.

Things get even more intense and complex when looking at the fishes’ lifelong habits. Building on Whitledge’s previous work, Valentine transects otolith samples with a laser before using a mass spectrometer to quantify the calcium, strontium and barium atoms present in each.

Like the rings of a tree, the ear stones maintain a record of the fish’s life from hatch to death.

Based on the elements it picks up from differing water chemistries in the Mississippi River and its tributaries, Valentine can determine where the fish was born and potentially moved to throughout its life.

“So, I can match the otolith chemistry to a potential water body’s chemistry to retroactively determine where a fish has lived during its life,” she said. “Shifts in otolith chemistry indicate movements to new water bodies.”

Big picture, big ideas

Pulling back and defining the context within which small interactions take place, and seeing how it all works together, is an important scientific approach, Valentine said.

“If you only focus on the very specific ideas that you can explicitly test with statistics, you’ll only get very specific answers to narrow questions, which would isolate the research,” Valentine said. “It’s critical to understand the big picture and how your work can be directly applied for the benefit of nature or humans, to know what future directions to go in and to understand the limitations of the work.”

Valentine’s work is part of a larger project in which teams of researchers from multiple universities and governmental agencies examine fish population structure, genetic structure and environmental history. The goal of the larger research project is to better understand how native fish persist in the Mississippi River. Scientists want to find out where the fish live, how certain places affect survival, size and age structure, and how the fish are genetically related to one another.

“Even though we work on our research projects independently, the goal is to come together later this summer to answer those big picture questions using our collected data,” Valentine said. “We aim to synthesize the research and provide applied results and recommendations to managers of the fish and Mississippi River and for publication in scientific journals.”

Looking ahead

Valentine said SIU has helped her learn much about her needs, goals, passions, likes, dislikes and boundaries as a scientist and individual. She plans to pursue a career in research and academiaw, mentoring students to help them learn about conserving the environment.

“I’ve learned I’m most passionate about we mentoring students, teaching, bettering myself and advancing science,” she said. “If I can combine these passions in any single career and help others feel comfortable and successful in science, I’ll feel accomplished.”