JEFFERSON CITY, Mo. — New research from the Missouri Hospital Association finds that in 2022, hospitals continued to struggle with finding and retaining staff, including nurses who comprise the largest single category of employee. Although turnover and vacancy rates among nurses and many of the other surveyed professions decreased in 2022, these costly and disruptive workforce challenges remain high — exceeding all survey years other than in 2021.

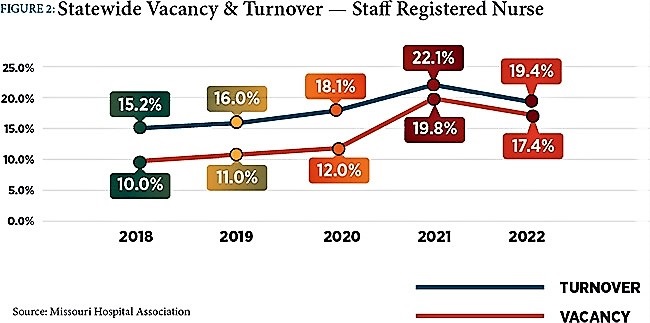

The 2023 MHA Workforce Report finds a nearly one-quarter turnover rate among all surveyed positions statewide, with more than 40% accounting for environmental services and dietary workers. The turnover rate among staff nurses was nearly 20% — one in five statewide. The nurse vacancy rate was more than 17%.

“The status of the health care workforce is a top concern for every hospital leader,” said Jon D. Doolittle, MHA President and CEO. “While this year’s data indicate a small improvement over the rates of vacancy and turnover experienced during the darkest days of the pandemic, they shouldn’t be viewed as an indicator that the hospital staffing crisis has passed. Much work remains to ensure hospitals have the staffing necessary to deliver and support care in the long and short term.”

The 2023 MHA Workforce Report includes statewide data on 28 hospital-based staff categories and four clinic and physician practice positions. The data also are available for 10 Workforce Development Regions and for the state’s critical access hospitals.

Although the statewide data help illuminate the status of the overall workforce, the regional data inform how variation exists within the communities where Missouri’s hospitals deliver care. For example, two regions — Southeast and South Central — have particularly troubling rates of turnover. Within each region, the report also identifies the 10-highest positions for vacancy and turnover. This can help hospitals, education leaders and other stakeholders understand the need for investment in specific areas and develop programs to address them, locally.

“There is no single solution to addressing this challenge,” Doolittle said. “It will require investment, innovation and the work of all stakeholders — including businesses and the public — to build the hospital workforce that is necessary to support hospitals and the state’s health care system. Some of these efforts will require local action.”

Several factors influence the workforce challenge. COVID-19 was very difficult for the health care workforce. Not only did the care environment change significantly with surges and lulls, but caregivers also were supplemented by costly agency staff, which distorted organizational processes and cultures — despite the benefit of the extra hands. A portion of these agency workers were Missouri’s own health care workers who shifted from their traditional employers to staffing companies. Some of these workers likely are returning to hospitals — which may be supporting the decrease in vacancy and turnover —while others continue in travel positions or have shifted to other parts of the workforce.

Presently, the pipeline for new workers is insufficient to deliver the workforce of the future. Without significant and ongoing investment, this will add to the supply and demand challenge for health care workers. In Missouri, an additional 64 full-time faculty positions would be necessary to accommodate all nursing school applicants who are qualified for admission. Each year, qualified nursing school applicants are turned away because of insufficient faculty. Moreover, without additional investment or innovative approaches to nurse training, the education system will struggle to replace the 98 Missouri nurse educators who are expected to retire within the next five years.

“Many health professions require post-secondary education,” Doolittle said. “In addition to attracting these future workers to positions as nurses, therapists, laboratory workers and technologists, Missouri’s technical schools, colleges and universities must be adequately tooled and staffed to train tomorrow’s health care workforce.

“Progress is being made. However, educator age and pay that favors clinical positions remain threats to worker pipeline expansion. Recent investments by state government are excellent steps toward growing the pool of workers and educators.”

Hospitals are looking internally as well as externally to build the skills and systems to ensure workers are available to deliver the care Missourians need, when they need it. Hospitals are working to upskill employees and create career ladders that not only build the workforce, but support lives and families. They are engaging with stakeholders — including but not limited to state government, academia and workforce development partners — to strengthen the system for attracting the next generation to health professions.

“This year’s workforce report is a reminder that we have work to do,” Doolittle said. “Every Missourian has a stake in the outcome. The good news is that health professions are rewarding, stable and diverse. Hospitals want to be the employer of choice in the communities they serve. It’s essential that more young people looking toward the future, and individuals looking to make both a change and a difference, know that caring for their family and neighbors is a great option.”

The Missouri Hospital Association is a not-for-profit association in Jefferson City that represents 141 Missouri hospitals. In addition to representation and advocacy on behalf of its membership, the association offers continuing education programs on current health care topics and seeks to educate the public about health care issues.